Kintsugi, the traditional Japanese art of repairing broken pottery, offers a profound lesson in embracing imperfections and appreciating life’s transient beauty. This unique art form is deeply rooted in the philosophies of wabi-sabi and mono-no-aware. Wabi-sabi finds beauty in imperfection and incompleteness, while mono no aware teaches the appreciation of life’s fleeting moments.

Kintsugi, which means ‘golden joinery’, uses gold powder to mend broken ceramics, highlighting rather than hiding their flaws. This approach not only restores the object but also transforms it, making its history and imperfections a part of its new beauty. In this article, we will explore how kintsugi, far more than a mere repair technique, embodies a philosophy that can inspire us to embrace our own flaws and the transience of life, seeing both as sources of beauty and strength.

II. What is Wabi-Sabi

Wabi-sabi(侘び寂び) is a profound and central philosophy in Japanese culture. It is a lens through which the beauty of the world, in its most raw and unrefined form, is appreciated and celebrated. This philosophy urges an appreciation for the imperfect and incomplete elements of existence.

Wabi-sabi originates from two Japanese words: “wabi(侘び),” which refers to rustic simplicity, quietness, and “sabi(寂び),” which means the beauty that comes with age. It’s about recognizing the beauty in the weathered and the worn, and the natural. Wabi-sabi finds elegance in asymmetry, roughness, and simplicity. It’s a counterpoint to the modern world’s relentless pursuit of perfection and symmetry, encouraging an appreciation for the unique and the irregular.

At its core, wabi-sabi is about embracing the natural cycle of growth and decay. It teaches us to appreciate the beauty in the fading leaves of autumn, the crack in an ancient piece of pottery, or the weathered face of an elderly person. These are not signs of decay to be overlooked or lamented, but are instead marks of life, experience, and authenticity.

In wabi-sabi, there is an acceptance that everything is in a constant state of change, and nothing lasts forever. This acceptance leads to a greater appreciation of the fleeting moments of beauty that life offers, encouraging us to slow down and find joy and contentment in the simple and unrefined.

In the context of kintsugi, wabi-sabi’s influence is evident. Kintsugi is the art of repairing broken pottery with gold powder and lacquer. This process highlights the cracks and breaks, not as flaws to be hidden, but as part of the object’s unique story and beauty. Kintsugi embodies the wabi-sabi philosophy by demonstrating that there is great beauty in embracing and celebrating the imperfections and storied history of an object.

In essence, wabi-sabi is not just a philosophy for appreciating art or aesthetics; it’s a profound perspective on life itself. It teaches us to embrace our imperfections, to see the transient nature of life as something beautiful, and to find harmony and peace in the simplicity and authenticity of our existence.

III. What is Mono-no-aware

Mono-no-aware(もののあはれ), can be translated to “aesthetic of impermanence” or “the pathos of things”. It is a philosophical concept deeply intertwined with Japanese culture and closely related to Kintsugi. This philosophy revolves around the poignant awareness of the transience and impermanence of all things in life.

Mono-no-aware teaches us to appreciate the beauty of fleeting moments and the emotional depth that comes from acknowledging the impermanence of existence. It encourages a profound sensitivity to the passage of time, the changing of seasons, and the inevitability of decay and loss. This heightened awareness of the impermanence of life fosters a deep sense of empathy and compassion for others, as we recognize that everyone and everything is subject to the same cycle of birth, growth, decline, and ultimately, transformation.

In the context of Kintsugi, mono-no-aware finds a natural connection. It symbolizes the idea that even in our brokenness and imperfections, there is a beauty and value that can be revealed. The repaired object, with its visible scars, becomes a poignant representation of the passage of time and the enduring spirit to persevere in the face of adversity.

Ⅳ. Connection Between Kintsugi and Tea Ceremony

The connection between Kintsugi and the culture of chanoyu (茶の湯: Japanese tea ceremony) is deeply rooted in the philosophy of wabi-sabi.

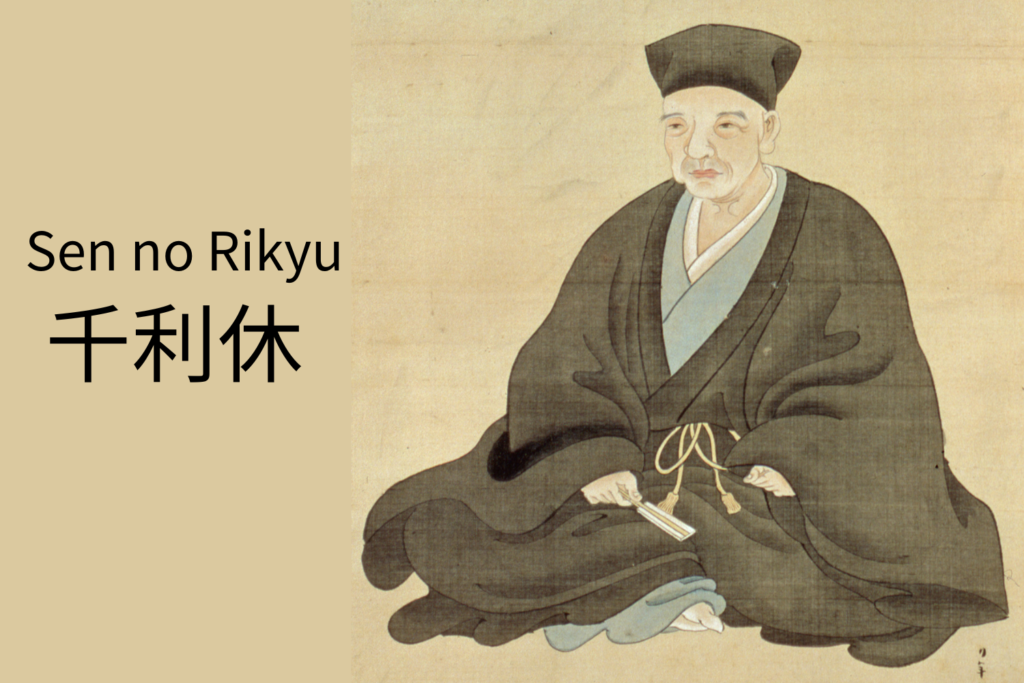

Chanoyu is more than just the act of drinking tea; it’s a Japanese tradition that seeks spiritual and meditative beauty. This culture was significantly shaped by Sen no Rikyu, a master of chanoyu in the 16th century. He established the style known as “wabi-cha”, which values simplicity and modest beauty, shunning elaborate and ornate sophistication in favor of imperfection and natural beauty. Sen no Rikyu taught that through chanoyu, one could seek a path to inner peace and spiritual elevation. Notably, Sen no Rikyu had a fondness for kintsugi bowls, contributing to the development and appreciation of this art form within the tea ceremony.

Kintsugi and chanoyu share the wabi-sabi philosophy of embracing the transient beauty and imperfection in things and finding richness in one’s inner self through this acceptance. Sen no Rikyu’s admiration for kintsugi bowls and his contributions to its development in the context of chanoyu further exemplify this connection. These traditions play a vital role in Japanese culture, significantly influencing the Japanese perception of beauty and way of life. Thus, kintsugi and chanoyu are interconnected through the philosophy of wabi-sabi, forming essential elements of Japan’s cultural identity.

Ⅴ. Wabi-Sabi and Mono-no-Aware Related Concepts

In the heart of kintsugi art lie the philosophies of Wabi-Sabi and Mono-no-Aware, which honor the beauty in imperfection and the fleeting nature of life. These concepts, deeply ingrained in the Japanese way of life, teach us to appreciate the transient beauty around us.

Let’s explore some essential terms that capture the spirit of these philosophies, offering insights into their profound and elegant teachings.

- 刹那 (Setsuna) – “Moment”: This term embodies the transient beauty of life and nature. Setsuna is a reminder to cherish the ephemeral moments, as they echo the wabi-sabi philosophy of finding beauty in fleeting experiences.

- 無常 (Mujō) – “Impermanence”: A core aspect of wabi-sabi, Mujō invites us to appreciate the beauty in the evolving, ever-changing aspects of life. It teaches the acceptance of life’s transient nature and the beauty that lies within it.

- 行雲流水 (Gyōun Ryūsui) – “Flowing Clouds and Water”: This phrase symbolizes the effortless and continuous flow of nature and life. It represents a harmony with the natural world, embracing change as an inherent part of existence.

- 粋 (Iki) – “Subtle Beauty”: Iki refers to a simple, understated elegance. It’s about an unobtrusive, subtle beauty that doesn’t seek attention, yet possesses a deep aesthetic value.

- 古色蒼然 (Koshoku Sōzen) – “Aged Appearance”: This term appreciates the beauty in aging. Koshoku Sōzen finds grace and nobility in the natural aging process of objects, highlighting their historical and emotional value.

- 自然体 (Shizentai) – “Naturalness/Spontaneity”: Shizentai speaks to the effortless state of being, an uncontrived simplicity that wabi-sabi highly values. It’s about being true to one’s nature, without pretense or artifice.

- 一期一会 (Ichigo Ichie) – “Once in a Lifetime Encounter”: This concept teaches the value of cherishing every moment and interaction as unique and unrepeatable. Ichigo Ichie is about mindfulness and appreciating the present, understanding the impermanent yet special nature of each experience in our journey through life.